The morality of push journalism in an algorithmic world

We live in a new era, the age of push journalism. This is a golden age, one in which we as consumers receive information seamlessly from a wide variety of sources. A quote in a New York Times article from 2008 sums up this idea nicely: “If the news is that important, it will find me.”

We allegedly have the free will to choose from among these sources to create the optimal mix of content that we can read, digest, and share with our peers. Pew Research found that a solid majority of consumers tend to get their news on the platforms they browse regularly. A bit tautological, but the basic premise is that consumers are not actively seeking out news the way that a person thirty years ago would have. It’s not about going to the newspaper stand, it’s about reading a post from The Atlantic after you’ve scrolled past a picture from your best friend on your News Feed.

But what happens if platforms such as Facebook do not offer an unbiased view of the news landscape? Does it fall back on us to know what has been omitted from our view?

How can we? It’s an impossible task.

Scroll through your Facebook page; do you think you are getting an unbiased view of the news? And I don’t mean what your friends are posting, I mean what Facebook itself is allowing you to see. Jay Rosen pointed out as much in an interview with WAN-IFRA last week. In his words, “Facebook has all the power. You have almost none.” We may be the recipient of content on Facebook’s news feed, but we are not necessarily the beneficiary. To put it another way, we’re not the consumers, we’re the product.

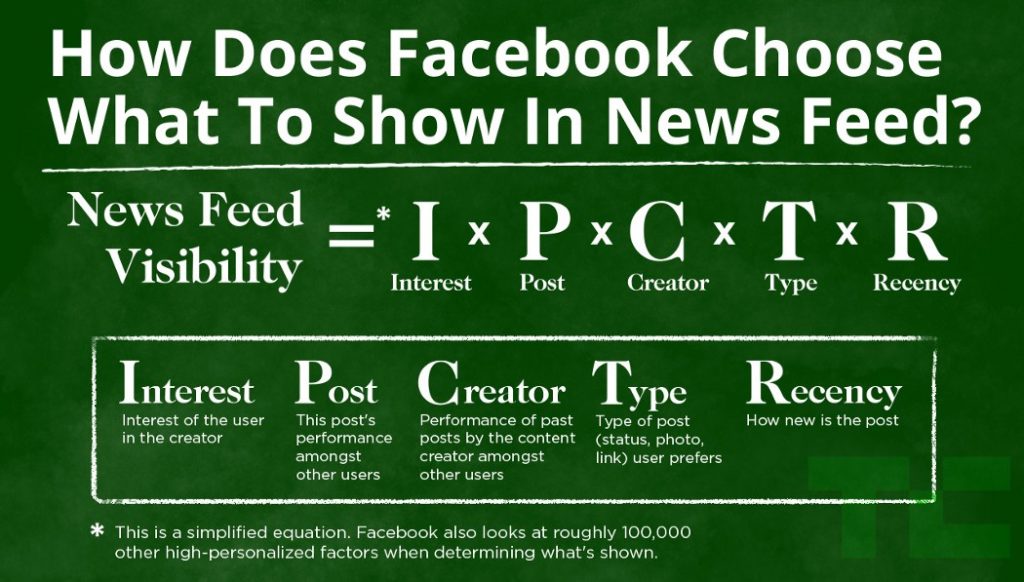

The nature of Facebook’s algorithm is opaque — we only know that it is curated for us, we rarely get to see behind that curtain. As a result, we are really experiencing an illusion of choice in our media consumption. Check out the asterisk at the bottom of this image from Techcrunch:

100,000 factors! This is the very definition of a black box system. As soon as your experience is curated by someone else, whether Facebook or another third-party, you lose a measure of choice. How can anyone guarantee that you are seeing what is most relevant to you? We have to trust that Facebook has our best interests in mind when curating for us. But do they?

This question has come to the fore in the scandal regarding Facebook’s experimentation with the content of its News Feed with respect to emotion. Not one of those in the sample group realized that they were seeing anything out of the ordinary. They did, however, experience a change in their emotional state that was outside of their control — a troubling implication.

Other platforms are not exempt from this issue either. Over the past year there have been allegations that Reddit’s code prevents certain types of posts from being seen early in their lifecycle. Not to mention the scandal of /r/technology moderators using their position to discriminate against topics ranging from Bitcoin to the NSA. Suffice it to say that Reddit is not in much of a better position than Facebook.

It’s worth pointing out that an opposite to Facebook’s approach is Twitter. On Twitter, everything is in your control (aside from a few well-marked Promoted posts). If you follow an account you will see all of their posts, and vice-versa. That’s not to say it is the perfect platform — following an increasing number of accounts can quickly become overwhelming — but at least in theory you remain in control of your feed’s content. You can’t say the same for other platforms.

What does this mean for consumers? The landscape really isn’t that different from the old age of analog news consumption: information has always been filtered, whether by editor or medium. The difference is that now filtering is specific to the individual as opposed to filtering across channels. Now that everyone is exposed to a different version of news, we need to adapt by being more deliberate in our news gathering methodology.

Ultimately, don’t count on any single platform to get your information. Social platforms can give us the illusion of choice, we may think that we’re being exposed to many different sources when in fact the limitations of their algorithms effect the opposite in practice. Be aware of the biases inherent in the platforms you use.

If we do this, then perhaps the negative aspects of the push journalism era can be mitigated.